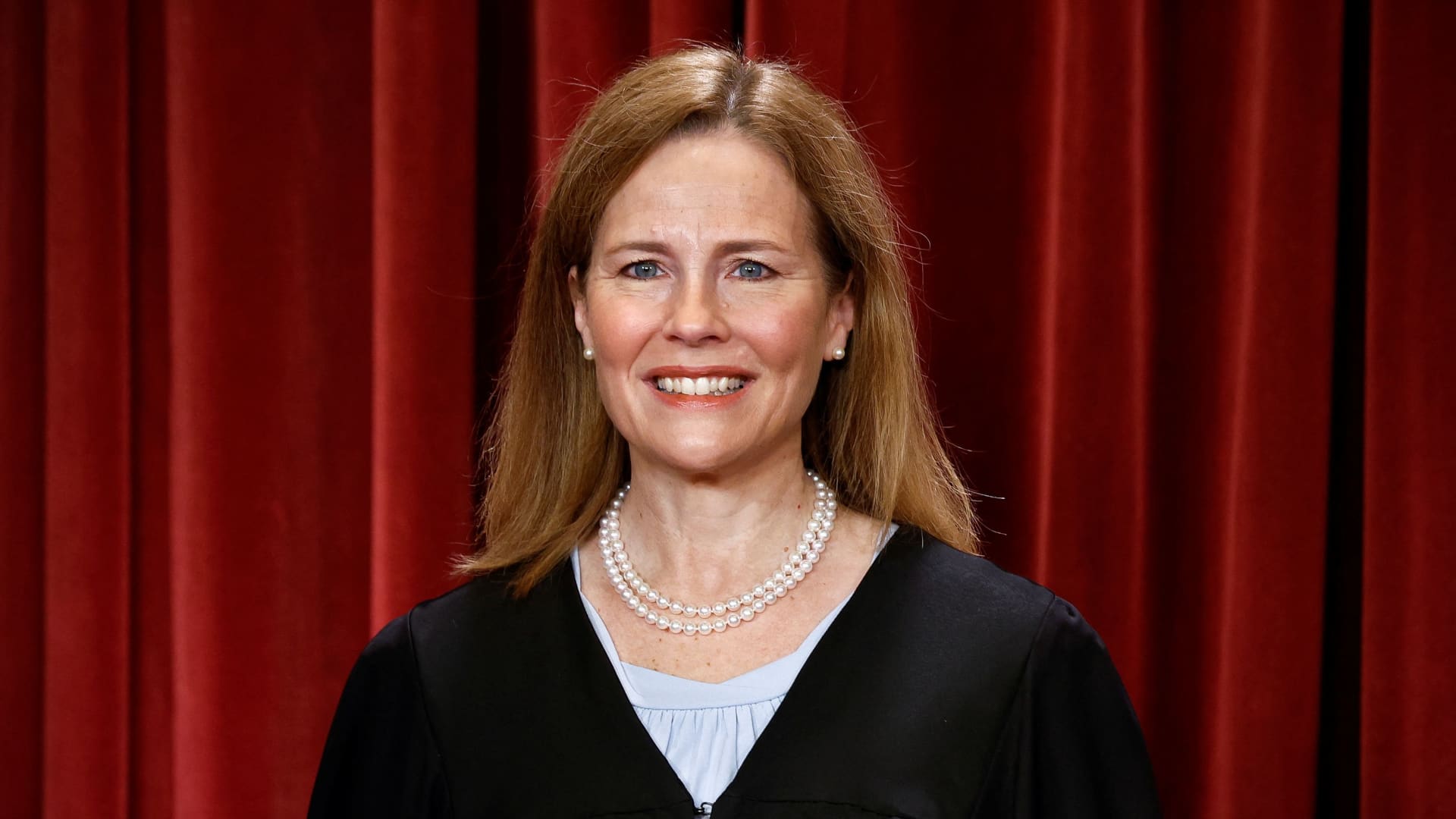

The fate of the Biden administration’s sweeping plan to cancel $400 billion in student loan debt for tens of millions of Americans may hinge on the newest conservative member of the Supreme Court: Justice Amy Coney Barrett.

Barrett was the conservative justice who seemed the most unconvinced by the plaintiffs challenging student loan forgiveness, said Jed Shugerman, a law professor at Fordham University. Specifically, Shugerman said, Barrett didn’t seem to agree that they’d proven they have standing to sue.

“Barrett was vocally and deeply uncomfortable about ruling that any of the plaintiffs had standing,” Shugerman said.

More from Personal Finance:

Why Social Security retirement age, payroll tax may change

Experts argue Social Security retirement age shouldn’t pass 67

Return on waiting to claim Social Security is ‘huge’

As a rule, plaintiffs must prove that a policy would cause them injury in order to challenge it in the courts.

That requirement, which has long been defended by conservative justices, especially former Justice Antonin Scalia, is meant to avoid people using the legal system to fight policies they do not like or agree with.

The six GOP-led states that brought a lawsuit against President Joe Biden‘s plan argue that the debt cancellation for up to $20,000 per borrower would decrease profits for companies in their states that service federal student loans. That argument has become focused on the Missouri Higher Education Loan Authority, or MOHELA.

Nebraska’s solicitor general, James Campbell, who argued on behalf of the states in front of the justices on Feb. 28, said Biden’s plan threatened to eat away at MOHELA’s operating revenue by as much as 40%.

Barrett seemingly unsatisfied by plaintiff arguments

But Barrett asked Campbell why MOHELA itself was not suing to block the plan instead of Missouri.

Officials at MOHELA recently said it had no involvement in Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt’s decision to sue against the program.

“Do you want to address why MOHELA’s not here?” Barrett asked.

Campbell replied, “MOHELA doesn’t need to be here because the state has the authority to speak for them.”

Barrett wasn’t satisfied by that answer.

“Why didn’t the state just make MOHELA come then?” she asked. “If MOHELA is really an arm of the state … why didn’t you just strong-arm MOHELA and say you’ve got to pursue this suit?”

Many commentators were asking, ‘Where is the Missouri SG?’ It’s like, Where’s Waldo?”Jed Shugermanlaw professor at Fordham University

Campbell answered: “Your honor, that’s a question of state politics.”

Shugerman, the law professor, said Campbell fumbled to explain how a loss in revenue for MOHELA would harm Missouri.

“The Nebraska solicitor general was unconvincing,” Shugerman said. “It was a mess.”

Shugerman also criticized the decision to have Nebraska’s top state attorney argue the case in front of the justices as opposed to the solicitor general of Missouri. He said that would have been appropriate because Missouri is the state with the best claim of an injury.

“Many commentators were asking, ‘Where is the Missouri SG?'” he said. “It’s like, ‘Where’s Waldo?'”

Plan’s survival depends on 2 conservative votes

Barrett alone can’t save the program.

The liberal justices — Elena Kagan, Ketanji Brown Jackson and Sonia Sotomayor — are almost certain to vote in favor of the plan, Shugerman said.

On the other hand, three conservative justices, Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch and Samuel Alito are likely to vote against it, he said.

Because of that, the Biden administration will likely need to convince not just Barrett but at least one of the other two conservative members of the court, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

“If she is a fourth vote, the question is, can she convince a fifth?” Shugerman said.

If the justices ignore the states’ lack of standing, they risk allowing any state or individual to challenge almost any federal program, said Steven Schwinn, a law professor at the University of Illinois Chicago.

“This is no way to run a federal democracy,” Schwinn said. “If the plaintiffs have a problem with loan cancellation, they should take it up through political processes.”