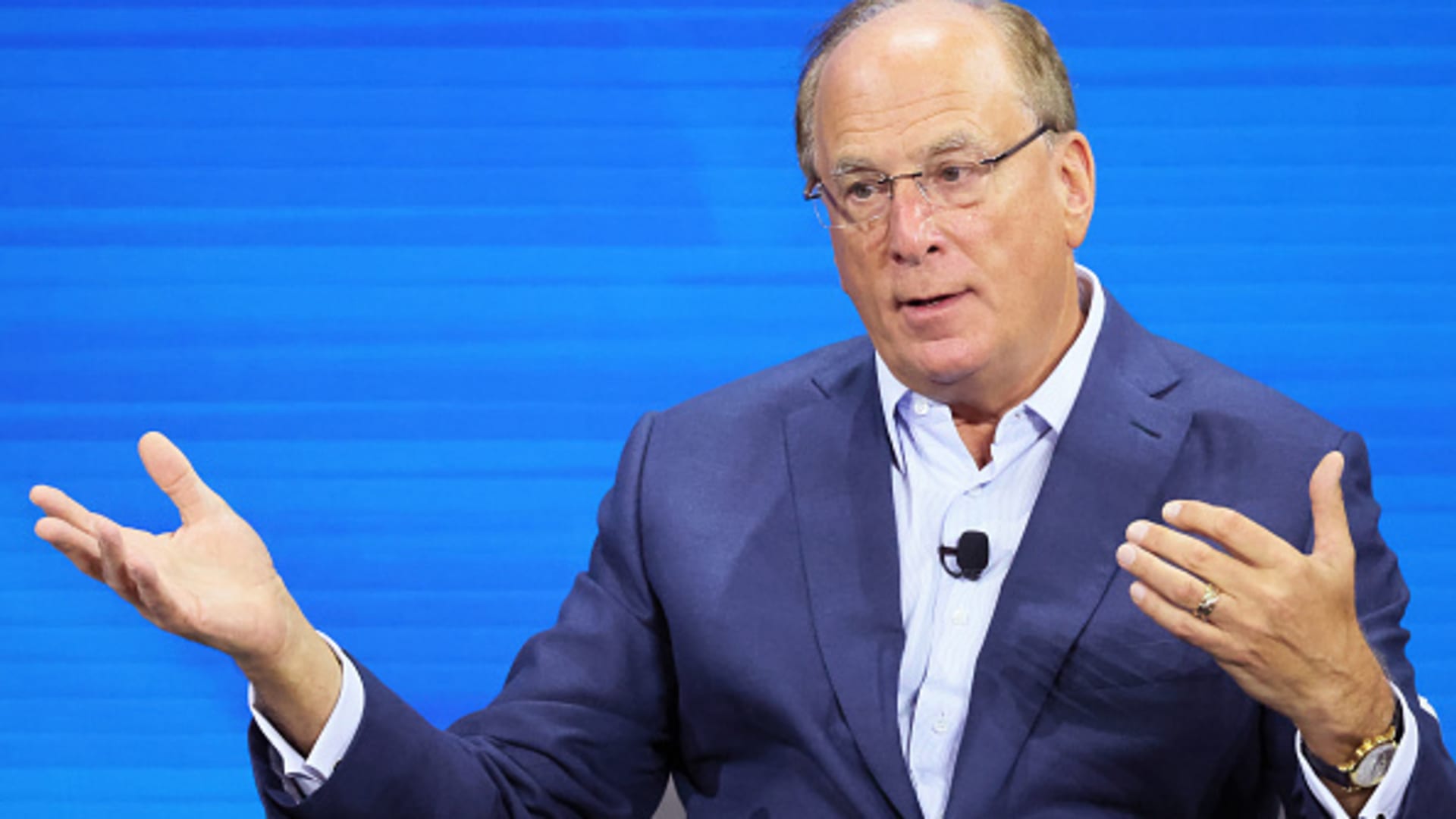

The idea of raising the Social Security retirement age has one more fan: BlackRock Chairman and Chief Executive Larry Fink.

“No one should have to work longer than they want to,” Fink recently wrote in an annual letter to investors.

“But I do think it’s a bit crazy that our anchor idea for the right retirement age — 65 years old — originates from the time of the Ottoman Empire,” wrote Fink, who is 71.

Republicans have touted raising the retirement age.

Former presidential candidate Nikki Haley said she would raise the Social Security retirement age for workers in their 20s. More recently, a House Republican budget proposal also called for lifting the age threshold for Social Security, though it did not specify by how much.

The reason for the suggestion largely comes down to demographics.

In the 1950s, many people who worked and paid into Social Security never lived long enough to retire and start receiving benefits, Fink noted.

Today, the chances are higher that certain retirees over 65 may still be collecting Social Security checks until age 90, he wrote.

Meanwhile, the number of baby boomers who reach age 65 is surging to historic levels. More than 11,200 Americans are expected to turn 65 every day — for a total of more than 4.1 million per year — from now through 2027.

More from Personal Finance:

Many Americans believe pensions are key to achieving the American Dream

Millionaires may have hit their 2024 Social Security payroll tax limit

78% of near-retirees failed or barely passed a basic Social Security quiz

That’s as Social Security is facing a looming shortfall. The trust fund used to pay retirement and survivors benefits is projected to run out in 2033, at which point there may be a benefit cut of at least 23%, Social Security’s board of trustees has projected.

“Age 65 is the anchor that is a cultural age which we have hung our retirement hat to for decades,” said Jason Fichtner, chief economist at the Bipartisan Policy Center and executive director of the Alliance for Lifetime Income’s Retirement Income Institute.

“It is no longer, I think, relevant,” he said.

How the Social Security retirement age may change

Today, a new Social Security full retirement age of 67 is still getting phased in, prompted by changes enacted by Congress in 1983.

Full retirement age is the point at which retirees stand to receive 100% of the benefits they’ve earned.

For many years, Social Security’s full retirement age was 65. Today, that is still the age when individuals become eligible for Medicare coverage.

Social Security benefits are available starting from age 62, “but with greater reduction” as a higher full retirement age phases in, according to the Social Security Administration.

Retirees who wait to claim until age 70 stand to get the biggest benefit — with an increase of up to 8% for each year they wait past full retirement age.

Yet fewer than 10% of claimants wait until that age, said Teresa Ghilarducci, a labor economist at The New School for Social Research and author of the book “Work, Retire, Repeat: The Uncertainty of Retirement in the New Economy.”

As lawmakers face a deadline to make changes and address the program shortfall, they generally may choose from a limited menu of options — hiking taxes, cutting benefits or a combination of both.

Social Security full retirement age

| Year of birth | Social Security full retirement age |

|---|---|

| 1943-1954 | 66 |

| 1955 | 66 and two months |

| 1956 | 66 and four months |

| 1957 | 66 and six months |

| 1958 | 66 and eight months |

| 1959 | 66 and 10 months |

| 1960 and later | 67 |

Raising the retirement age, which is often presented as another option, is really a benefit cut, said Alicia Munnell, director of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

“When you change the retirement age, it’s particularly painful to those who have to keep retiring at 62, people with health issues or people in professions where no jobs are available,” Munnell said.

Congress may eventually raise the full retirement age to 69, predicts Andrew Biggs, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, even though Democrats have promised not to make that change.

“When you look at countries around the world that have had underfunded pension systems, they raise the retirement age,” Biggs said. “It’s just a very, very common fix.”

For each year the Social Security full retirement age is increased, that would cut benefits by a little under 7%, Biggs said.

Pushing the age to 69 would repair less than one-fifth of Social Security’s shortfall, so other reforms would also be necessary, Biggs said. Moreover, a new higher retirement age would have to be phased in much faster than the 40-year window used for the last increase, he said.

Experts have other changes on their wish lists

Researchers and policy experts who have spent years studying Social Security’s shortfall have their own wish lists for the changes they would make.

Fichtner, who supports raising the retirement age, said that change would need to be paired with a higher minimum benefit, so as not to punish workers who cannot work longer.

“Some people have the ability to work, some people want to work, but some people can’t,” Fichtner said. “It’s important that we maintain a healthy minimum benefit amount at age 62.”

Increases to the retirement age could be set to automatically adjust to changes in longevity, much as the annual Social Security cost-of-living adjustments are tied to inflation, he said.

Other experts would opt for different changes in place of raising the retirement age.

Biggs advocates for moving to one flat benefit for all retirees, similar to what Australia provides. If that change were put in place, raising the retirement age would be unnecessary, he said.

Munnell argues the most effective benefit cut would be to reduce the replacement rates for higher-income workers.

Ultimately, workers want to retire on their own terms — at the age they want and with enough money to live comfortably.

To make that more possible, employers need to engage older workers so they feel comfortable staying in the workforce, said David Blanchett, managing director and head of retirement research at PGIM DC Solutions.

“There’s still potentially some implicit bias towards older Americans leaving the workforce,” Blanchett said. “If we can have a president over the age of 75 or 80, I think as a society we should be able to find more ways to accommodate older workers.”