The latest inflation report confirms that prices for just about everything continue to rise, with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) up 8.3 percent over the last year and many categories up even higher, including food (11.4 percent) and energy (23.8 percent). While not part of the CPI, another measure of inflation (call it the Taxpayer Price Index?) is also surging: federal tax collections are up 23 percent over the last year, according to the latest data from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). At the current pace, federal tax collections will reach a record high of about $5 trillion in nominal dollars for the fiscal year (FY) 2022 ending September 30, which is about $1 trillion more than last year’s $4 trillion in collections (also a record).

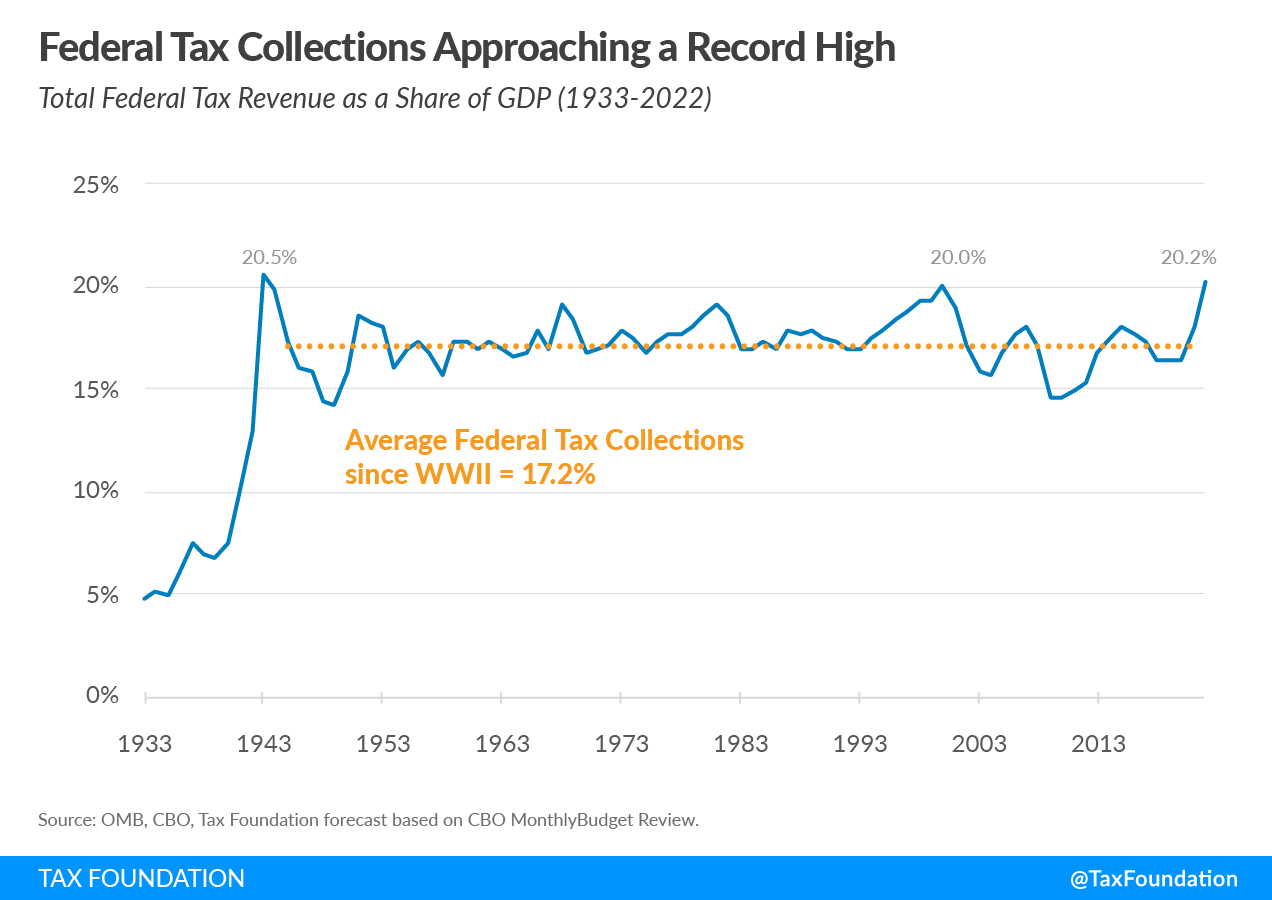

As a share of GDP, federal tax collections are on track to hit a multi-decade high of about 20.2 percent in FY 2022, up from 18.1 percent last fiscal year and exceeding the last peak of 20 percent set during the dot-com bubble in FY 2000. Federal tax collections are approaching the all-time high of 20.5 percent of GDP set in 1943 during World War II. Compared to average federal tax collections in the post-war era of 17.2 percent of GDP, this year’s collections are set to exceed that level by 3 percentage points.

Looking at federal tax collections in the current fiscal year to date (11 out of 12 months are in), individual income tax collections have surged the most, up 32 percent from $1.8 trillion last year to $2.4 trillion this year. This is perhaps partly due to capital gains resulting from last year’s booming stock and housing markets. Payroll taxes are up 14 percent from $1.2 trillion last year to $1.4 trillion this year, while corporate taxes are up 12 percent from $285 billion to $319 billion. Other revenues are up 17 percent from $281 billion to $328 billion.

Extreme economic volatility in recent years makes it difficult to assess how tax collections have been impacted by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) enacted in 2017. Among other changes, the TCJA reduced the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. Corporate and other federal tax revenues were relatively low in 2018 through the first year of the pandemic but have since rebounded with the economy and inflation. Average federal tax collections in the five years since the TCJA’s enactment are about 17.5 percent of GDP, higher than the 16.7 percent forecasted by the CBO following its passage, higher than most years before the TCJA, and higher than the post-war average of 17.2 percent.

Note that current tax collections do not reflect the tax changes enacted last month as part of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which mostly goes into effect beginning January 1, 2023. We estimate the IRA will increase gross revenue by about $28 billion in 2023, offset by $39 billion of tax credits, which is small relative to the budgetary effects of inflation and the rebounding economy.

It remains to be seen where tax revenue will go from here, but it clearly depends on the direction of the economy and inflation—and how potential policy changes affect both. This highlights the need for policymakers to at least try to account for these effects when weighing various policy trade-offs.

Furthermore, policymakers should seriously consider giving taxpayers a break, both in terms of taxes and spending. Record federal tax collections on top of surging prices—essentially an additional inflation tax paid by everyone who uses dollars—should not be used as a justification for more spending. Indeed, excessive spending in response to the pandemic is driving inflation, and rather than ramping up expensive relief programs (e.g., student loan forgiveness), we should be winding them down. Taxpayers should demand that pandemic emergency spending end now that the pandemic emergency is over, and that their tax dollars be used more judiciously or returned to them.