“Frothy eloquence neither convinces nor satisfies me,” the 19th century Congressman Willard Duncan Vandiver allegedly declared. “I am from Missouri. You have got to show me.”

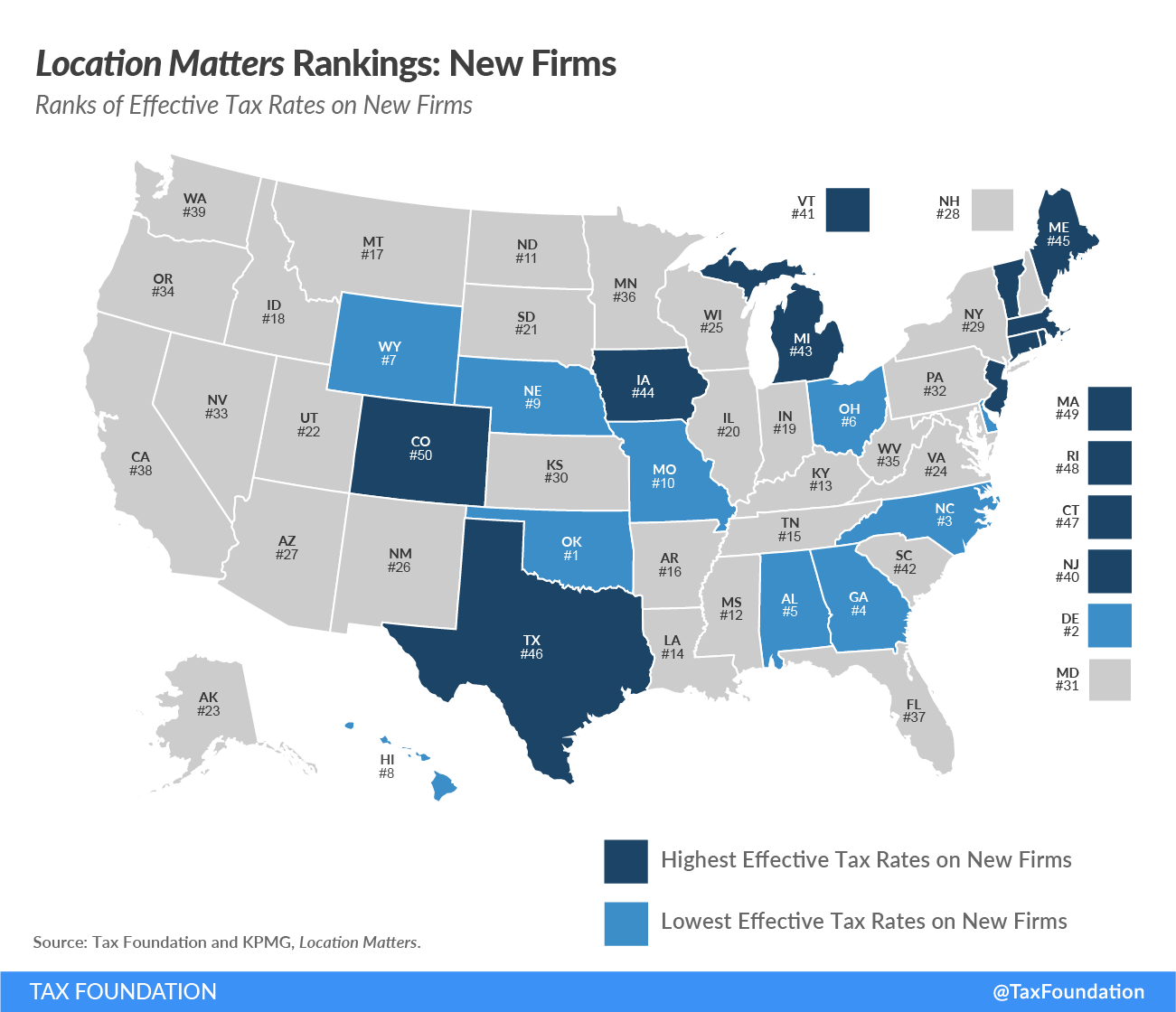

In the realm of tax policy and economic competitiveness, lawmakers from the Show-Me state are turning the old adage around. They are showing the rest of the nation how to create a more competitive tax code—one that now offers the tenth-lowest effective rates for new businesses, according to a new analysis conducted by the Tax Foundation and KPMG LLP.[1]

As a state, Missouri has not always marched in step with its peers on tax policy. It was the last state to adopt economic nexus standards for its sales tax in the wake of the South Dakota v. Wayfair decision, and it is one of a dwindling number of states to still offer a deduction for federal taxes paid. But when Missouri has acted, it has done so decisively, and frequently in ways that have benefited taxpayers. When the state did adopt a post-Wayfair remote sales tax regime, it took the opportunity—neglected almost everywhere else—to use the additional revenue to pay down income tax rate reductions, for instance.

Additional ones, really, since the state had already embarked on previous efforts to bring down rates and enhance its tax competitiveness, including reforms yielding a highly competitive 4 percent corporate income tax rate with apportionment rules that favor in-state investment. And for pass-through businesses, which pay through the individual income tax code, legislation adopted in 2014, 2018, and 2021 will ultimately drop the top individual income tax rate to 4.8 percent, from a starting point of 6 percent.[2]

All this is good news for businesses and individuals in Missouri. While work remains to be done, the progress is evident, as the Tax Foundation’s Location Matters study shows.

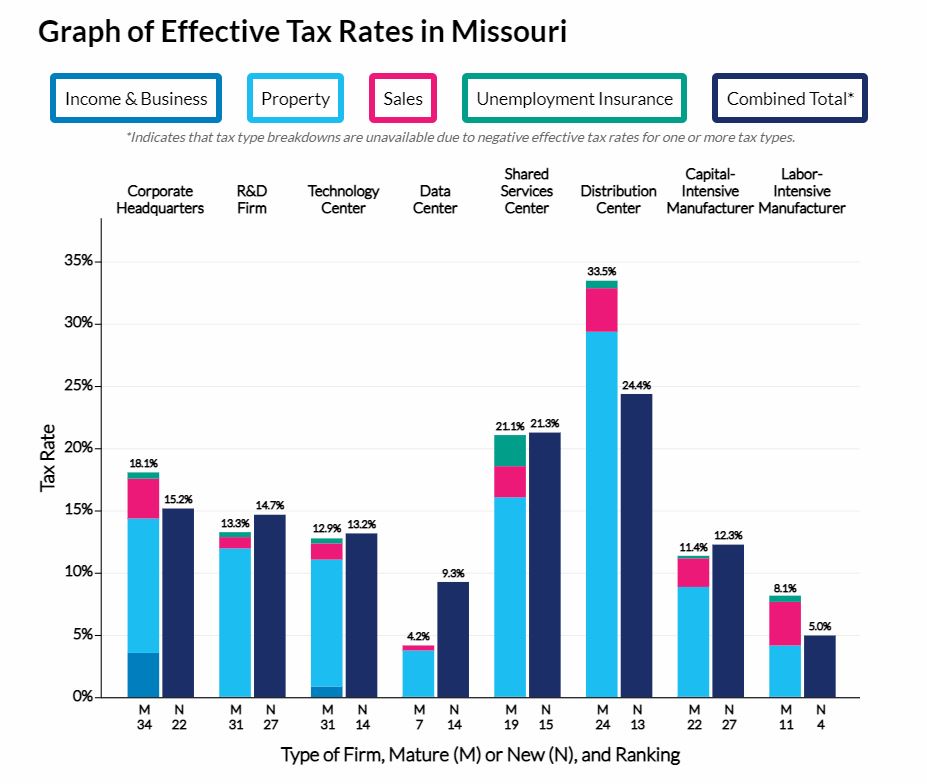

Location Matters compares corporate tax costs in all 50 states across eight model firms: a corporate headquarters, a research and development facility, a technology center, a data center, a shared services center, a distribution center, a capital-intensive manufacturer, and a labor-intensive manufacturer. Each firm is modeled twice, first as a new operation eligible for tax incentives and then as a mature operation not eligible for such incentives.

Missouri offers particularly attractive tax rates to data centers, shared services centers, and labor-intensive manufacturers, as well as newly established technology centers, due to certain aspects of the state’s tax structure. While most other firms experience more middle-of-the-pack burdens, Missouri is notable for avoiding disproportionately high taxes on any of the industries we studied. No mature firm is ranked worse than 34th, and no new operation worse than 27th. Consequently, the state ranks 10th overall for new operations and 18th for mature firms.

| Rank | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | New | Mature |

| Missouri | 10 | 18 |

| Arkansas | 16 | 33 |

| Illinois | 20 | 46 |

| Iowa | 44 | 42 |

| Kansas | 30 | 50 |

| Kentucky | 13 | 15 |

| Nebraska | 9 | 9 |

| Oklahoma | 1 | 10 |

| Tennessee | 15 | 8 |

|

Source: Tax Foundation, Location Matters. |

||

Two neighboring states—Nebraska and Oklahoma—provide more competitive overall tax rates to newly established firms, while four of Missouri’s eight border states—Kentucky, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Tennessee—outperform Missouri in rates on mature firms.

Missouri sources services where the benefits are received, which is to the advantage of firms like shared services centers, and the state exempts manufacturing machinery from the sales tax, which lowers tax costs for both capital- and labor-intensive manufacturing companies. For many firms, particularly those with sales largely out of state, income tax burdens are negligible. Property taxes can be substantial for some firms, however, and the state sales tax rate is above-average, which offsets some of the benefit provided by modest income taxes. However, local jurisdictions have the ability to abate property taxes for certain competitive investments. And in many cases, both state and local entities can also exempt sales taxes through various incentive programs.

Notably, Missouri has split roll property taxation, meaning that commercial property faces higher effective rates than similarly valued residential property. Business machinery and equipment is also subject to property taxes, though, like most states, Missouri exempts inventory. While uncommon, inventory taxation is practiced by three of Missouri’s neighbors (Arkansas, Kentucky, and Oklahoma).

| Income & Business Taxes | Property Taxes | Sales Taxes | UI Taxes | Total Effective Tax Rate | Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate Headquarters | ||||||

| Mature | 3.6% | 10.8% | 3.2% | 0.5% | 18.1% | 34 |

| New | -2.2% | 12.4% | 4.5% | 0.5% | 15.2% | 22 |

| Research & Development | ||||||

| Mature | 0.1% | 11.9% | 0.9% | 0.4% | 13.3% | 31 |

| New | -4.0% | 16.7% | 1.4% | 0.5% | 14.7% | 27 |

| Technology Center | ||||||

| Mature | 0.9% | 10.2% | 1.3% | 0.4% | 12.9% | 31 |

| New | -8.5% | 16.1% | 5.1% | 0.6% | 13.2% | 14 |

| Data Center | ||||||

| Mature | 0.1% | 3.7% | 0.4% | 0.0% | 4.2% | 7 |

| New | -0.2% | 8.3% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 9.3% | 14 |

| Shared Services Center | ||||||

| Mature | 0.1% | 16.0% | 2.5% | 2.5% | 21.1% | 19 |

| New | -7.7% | 20.8% | 5.0% | 3.1% | 21.3% | 15 |

| Distribution Center | ||||||

| Mature | 0.0% | 29.4% | 3.5% | 0.6% | 33.5% | 24 |

| New | -1.9% | 19.0% | 6.5% | 0.7% | 24.4% | 13 |

| Capital-Intensive Manufacturer | ||||||

| Mature | 0.1% | 8.8% | 2.3% | 0.2% | 11.4% | 22 |

| New | -1.4% | 10.6% | 2.8% | 0.2% | 12.3% | 27 |

| Labor-Intensive Manufacturer | ||||||

| Mature | 0.1% | 4.1% | 3.5% | 0.5% | 8.1% | 11 |

| New | -5.1% | 5.0% | 4.5% | 0.6% | 5.0% | 4 |

|

Source: Tax Foundation, Location Matters. |

||||||

Whereas in some states, business owners have reason to fear that tax burdens will increase, Missouri has demonstrated a commitment to tax reform in recent years, with additional tax relief continuing to phase in. Most businesses—as well as individuals—can expect an increasingly competitive tax environment in the coming years.

In 2014, lawmakers implemented cautious revenue triggers which, if met, would phase down the top individual income tax rate, in 0.1 percentage point increments, from 6 to 5.5 percent. In 2018, after the first phasedown to 5.9 percent, lawmakers accelerated the process using revenue from base broadening due to the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the definitions from which flowed through to state taxes. At the time, lawmakers implemented the 5.5 percent rate but left the remaining triggers in place, holding out the prospect of bringing the rate as low as 5.1 percent. While many other states were content to keep revenue windfalls from federal tax reform, Missouri lawmakers returned it to taxpayers.[3]

In 2021, with revenues continuing to tick upward despite the global pandemic, and with additional revenue anticipated from the state’s expansion of sales tax nexus to remote sellers, lawmakers further revised their targets, extending and revising revenue triggers to ultimately drop the individual income tax rate to 4.8 percent. Time and again, Missouri policymakers have acted to return at least a portion of anticipated revenue growth to the taxpayers—particularly where the individual income tax is concerned, which is of considerable interest to the 96 percent of Missouri businesses which are structured as S corporations, partnerships, limited liability corporations, or sole proprietorships, and thus file through the individual income tax code.[4]

Traditional C corporations have not, however, been neglected. In 2018, the legislature cut the corporate income tax rate from a middle-of-the-pack 6.25 percent to a highly competitive 4 percent, which is currently tied for second lowest in the nation, with Oklahoma. (North Carolina, at 2.5 percent, has the lowest-rate corporate income tax of states imposing one.) The rate reduction was paid for with structural reforms, namely repealing an anachronistic policy of federal deductibility while requiring the use of a uniform apportionment factor.

Under federal deductibility—now repealed for corporate taxpayers and curtailed, but not eliminated, for individual filers—taxpayers could deduct their federal tax liability from state taxable income. This was a way of reducing state tax liability, but one far inferior to a lower rate, because it tied Missouri’s tax code to federal policy in unexpected and often undesirable ways. When federal taxes went down, Missouri taxes went up. When the federal government provided preferential treatment of something, Missouri penalized it. So when, for instance, the federal government improves its treatment of capital investment, or provides a credit for research and development expenditures, a policy of federal deductibility yields the inverse treatment at the state level, increasing taxes on those activities.

Replacing federal deductibility with lower rates has improved Missouri’s corporate tax structure, and the same could be true for individual taxpayers if it were fully repealed within the individual income tax as well. While the individual income tax does not affect the traditional C corporations analyzed in Location Matters, it matters to many Missouri employers.

Missouri’s improved tax climate is reflected not only in Location Matters but in other studies as well, including the Tax Foundation’s State Business Tax Climate Index and CNBC’s “America’s Top States for Business” rankings. Since Missouri’s tax reforms began to phase in, the state has improved from 18th to 10th on the “Economy” subcomponent of CNBC’s rankings and from 17th to 5th on the cost of doing business,[5] while improving from 16th to 12th overall on the State Business Tax Climate Index, which measures tax structure. In particular, Missouri now boasts the best corporate tax structure of any state with a corporate income or gross receipts tax, and has the fourth-best overall ranking among states with all the major state-level taxes (individual income tax, corporate income tax, and sales tax), after Utah, Indiana, and North Carolina.[6]

While Missouri has room for improvement, the state is making waves, positioning itself as an increasingly attractive location for business investment. And as ongoing reforms further enhance the competitiveness of the state’s tax code, more businesses will take notice.

[1] Jared Walczak et al., Location Matters 2021: The State Tax Costs of Doing Business, Tax Foundation, May 5, 2021, https://www.taxfoundation.org/state-tax-costs-of-doing-business-2021/.

[2] Katherine Loughead and Jared Walczak, “States Respond to Strong Fiscal Health with Income Tax Reforms,” Tax Foundation, July 15, 2021, https://www.taxfoundation.org/2021-state-income-tax-cuts/.

[3] Jared Walczak, “Missouri Governor Set to Sign Income Tax Cuts,” Tax Foundation, July 11, 2018, https://www.taxfoundation.org/missouri-governor-set-sign-income-tax-cuts/.

[4] Internal Revenue Service, “IRS Data Book, 2020,” https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-irs-data-book-index-of-tables; and Tax Foundation calculations.

[5] CNBC, “America’s Top States for Business 2021,” July 13, 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2021/07/13/americas-top-states-for-business.html (and prior years).

[6] Jared Walczak and Janelle Cammenga, 2021 State Business Tax Climate Index, Oct. 21, 2020, https://www.taxfoundation.org/2021-state-business-tax-climate-index/.