Tackling climate change and shifting the economy towards renewable energy has been a key part of the Biden administration’s agenda. However, this effort must first confront an overly complicated and non-neutral tax code, particularly in how it treats nuclear energy, for the White House to reach its ambitious goal of a 100 percent clean energy sector by 2035 and economy-wide net-zero emissions by 2050.

As the world’s largest nuclear power producer, American reactors provide one-fifth of the nation’s overall electricity and represent over half of the nation’s total emission-free electricity, with nuclear power plants located in more than 30 states. Each nuclear facility, on average, generates approximately $470 million in annual sales and provides almost $40 million in wages to a workforce of one-third union-affiliated workers. The average plant pays upwards of $67 million annually in federal taxes and almost $16 million to state and local governments.

However, nuclear energy has not expanded as a share of domestic power generation. Due to a near halt in new construction in the past 30 years, almost all U.S. nuclear-generating capacity comes from plants built between 1967 and 1990. The U.S. is home to 93 operating reactors, down 11 since 2013. The last three years have seen the premature closure of plants that produced enough carbon-free electricity to power the equivalent of 4 million gasoline-powered cars.

The industry has faced competition from other renewables, which enjoy extensive preferences in the tax code. An energy sector crowded with energy sources that charge sub-market prices due to government subsidies such as tax credits creates steep competition for nuclear energy and has resulted in a staggering number of premature reactor retirements. Renewable energies, like solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, and biomass, have earned a sharp increase in market share. Modern renewable energies made up over 17 percent of electricity production in 2018, thanks to growth in wind, hydro, and biomass. As renewable energy consumption has grown 13.7 percent annually on average over the past decade, conservative estimates expect a quarter of U.S. energy production coming from modern renewables by 2030.

The federal government supports energy technology development through two main paths: tax credits and government spending. R&D tax credits allow companies to claim spending on qualified research expenditures (QREs) against their taxable income on their annual returns. The Department of Energy also supports energy innovation directly, spending around $8 billion in 2020 on total energy R&D, with about $1.5 billion of that on nuclear energy, primarily in the form of grants and loans.

Direct subsidies towards the energy sector materialize through two tax credits. Production tax credits (PTCs), as the most prominent targeted tax policy, grant cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh) of energy produced by a particular energy source. On the other hand, investment tax credits (ITCs) allow companies to reduce their total tax liability by a certain percent of the money they spend on investment in renewables. ITCs mostly benefit solar, unlike PTCs, which typically benefit wind energy.

The Renewable Electricity Production Tax Credit (also known as Section 45) is an at most 2.5 cents per kWh tax credit for electricity generated for the first 10 years by facilities using qualified energy resources, adjusted annually for inflation. The qualifying time schedule and resource list has been expanded 12 times and remains available to projects under construction prior to December 31, 2020. The Energy Investment Tax Credit provides a 30 percent tax credit for investments in renewable energy projects that began construction in 2019 and are scheduled to come online by 2023, and currently provides a 26 percent tax credit for projects beginning construction before the end of 2022. It is scheduled to continue phasing down until the end of 2023, when solar and geothermal facilities will receive a permanent 10 percent credit. The production tax credit primarily benefits wind energy, while the investment tax credit primarily benefits solar.

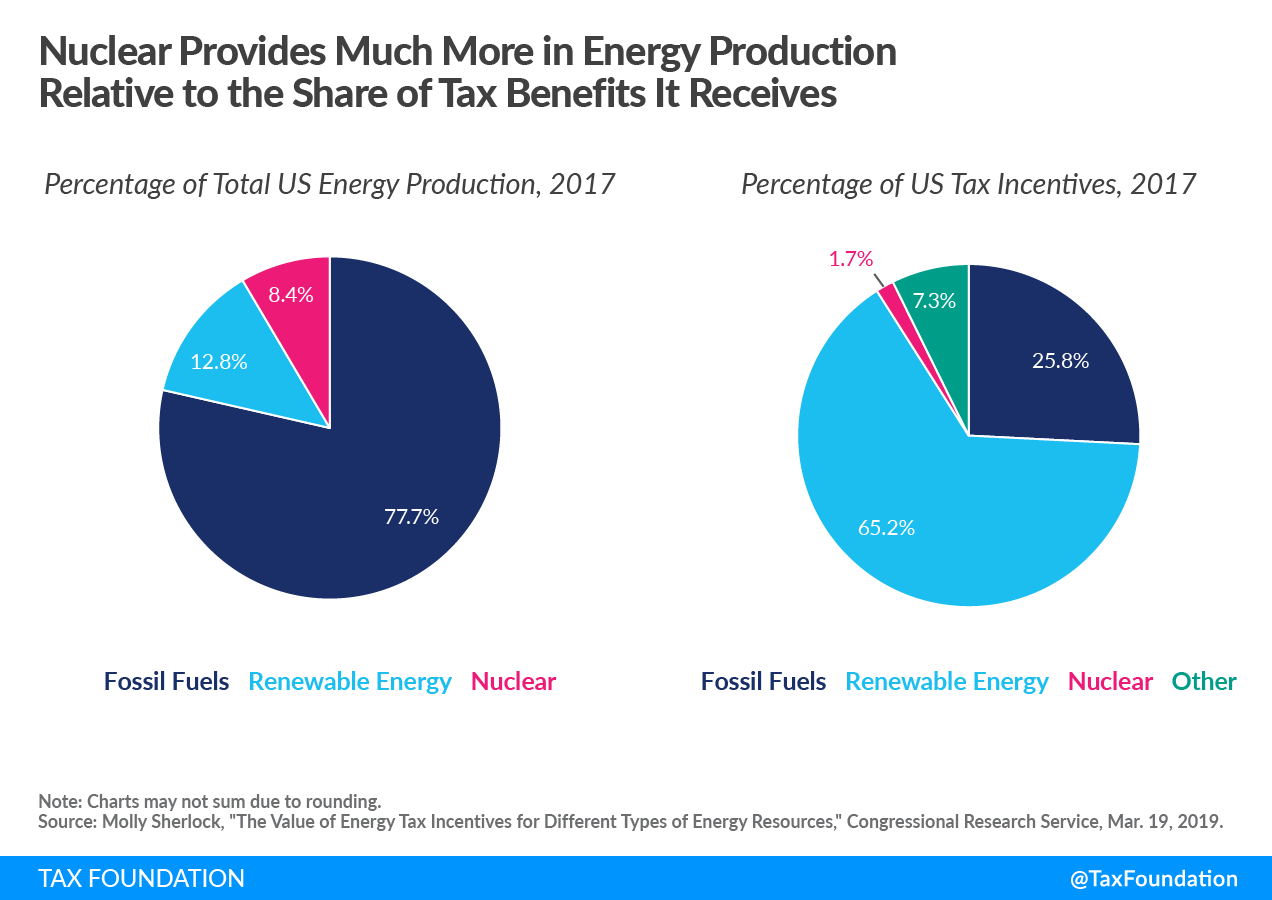

Nuclear energy is not included in either tax credit. In 2018, nuclear energy received only roughly $100 million in tax benefits, compared to roughly $9.5 billion for renewables. Nuclear has received a significant share of direct federal support: almost half of all federal R&D spending towards energy sources have gone to nuclear since 1950. However, direct R&D expenditures have declined substantially since the mid-20th century, and renewables now surpass nuclear in direct federal aid. Nuclear R&D also gets some support from R&D tax credits (both for general R&D and the credit specifically for energy research).

While there remains no existing ITC directly available to reactors, the nuclear sector does receive the much smaller and currently unused Nuclear Production Tax Credit. First established in the 2005 Energy Policy Act, the PTC credits 1.8 cents per kWh of electricity produced during the first eight years of operation by advanced nuclear power facilities. The credits include limitations: it is available for up to 6,000 megawatts (MW) nationwide, on a first-come-first-serve basis, and is not adjusted for inflation. Originally available to facilities entering commercial operations by December 2020, the PTC has received another conditional extension, to include two eligible nuclear facilities that have experienced sluggish construction.

There is one other important dimension to the tax treatment of nuclear energy: cost recovery. For most investments, the IRS requires companies to spread out the cost of investments over several years, to approximate their useful life. However, this is not ideal: spreading out the cost of capital investment means that companies cannot deduct the full real value of investment costs, as inflation and the time value of money reduce the value of future deductions. This imbalance creates a tax bias against capital-intensive companies, when physical capital constitutes a higher portion of their costs relative to labor (which can be deducted immediately).

That matters for nuclear energy in particular. Nuclear energy has extremely high capital costs, relative to even other energy sources. As such, by stopping short of full expensing—a tax system where all investments can be deducted immediately—the tax system disproportionately harms nuclear power generation (and other forms of green investment). The tax code does allow for the accelerated depreciation of some form of nuclear power investment, by allowing assets used in the construction of nuclear power facilities to be depreciated over 15 years instead of 20. However, ideally, those investments would be deducted immediately.

In Congress, several legislative proposals have been introduced to provide targeted support to the struggling nuclear base. Notably, the bipartisan infrastructure bill includes $6 billion in support for aging nuclear power plants. Introduced in 2019, the Nuclear Powers America Act (NPAA) would extend the ITC benefits of IRC Section 48 to carbon-free nuclear power facilities and be applied toward refueling costs and other qualified capital expenditures. The American Nuclear Infrastructure Act (ANIA) would establish a program to evaluate current nuclear facilities facing operational closures and provide a corresponding PTC based on a reactor’s operating loss over a four-year period.

Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR), along with 24 colleagues, reintroduced the Clean Energy for America Act. The bill would consolidate the existing 44 “tax breaks” in the overall energy sector and replace them with only three technology-neutral credits: a 2.5 cents per kWh production tax credit or 30 percent investment tax credit for electricity generation plants with zero or net negative carbon emissions; a tax credit for fuels that are 25 percent cleaner than average; and a credit for the construction of new energy-efficient homes as well as for the retrofitting of existing buildings, residential and commercial.

Ultimately, the best improvement to the tax code for nuclear energy would be establishing full expensing for capital investment, which would help nuclear energy among other capital-intensive industries, like manufacturing, more generally. As long as policymakers use the tax code to provide additional support for non-carbon-emitting energy, it would make sense to equalize treatment for nuclear energy relative to solar and wind while simplifying the many tax credits aimed at nuclear and renewable energy.

Was this page helpful to you?

Thank You!

The Tax Foundation works hard to provide insightful tax policy analysis. Our work depends on support from members of the public like you. Would you consider contributing to our work?

Contribute to the Tax Foundation

Share This Article!

Let us know how we can better serve you!

We work hard to make our analysis as useful as possible. Would you consider telling us more about how we can do better?